- Home

- Niccolò Ammaniti

I'm Not Scared Page 5

I'm Not Scared Read online

Page 5

The lake, we called it.

There were no fish in it, nor tadpoles, only mosquito larvae and water boatmen. If you put your feet in it, you took them out covered in dark, stinking mud.

We went there for the carob.

It was big, old and easy to climb. We dreamed of building a tree house on it. With a door, a roof, a rope ladder and all the rest. But we had never been able to find the planks, the nails, or the skill. Once Skull had fixed a bedspring up there. But it was very uncomfortable. It scratched you. Tore your clothes. And if you moved too much you were liable to fall out.

Lately the others had stopped climbing the carob. I still liked it, though. I felt good up there in the shade, hidden among the leaves. You could see a long way, it was like being at the top of a ship’s mast. Acqua Traverse was a tiny patch, a dot lost in the wheat. And you could keep watch over the Lucignano road. From there I could see the green tarpaulin of papa’s truck before anybody else.

I climbed up to my usual place, astride a thick branch that forked out, and decided I would never go home again.

If papa didn’t want me, if he hated me, I didn’t care, I would stay there. I could live without a family, like the orphans.

‘I don’t want you. Get out.’

All right, I said to myself. But when I don’t come back you’ll be sorry. And then you’ll come under the tree and ask me to come back but I won’t come back and you’ll beg me and I won’t come back and you’ll realize you were wrong and your son won’t come back and he lives on the carob.

I took off my T-shirt, rested my back against the wood, my head in my hands, and looked at the hill where the boy was. It was far away, at the end of the plain, and the sun was setting beside it. It was an orange disc that faded to pink against the clouds and the sky.

‘Michele, come down!’

I woke up and opened my eyes.

Where was I?

It took me a few moments to realize I was perched on the carob.

‘Michele!’

Under the tree, on her Graziella, was Maria. I yawned. ‘What do you want?’ I stretched. My back was all stiff.

She got off her bike. ‘Mama said you’ve got to come home.’

I put my T-shirt on again. It was beginning to get cold. ‘No, I’m not coming home, tell her. I’m staying here!’

‘Mama said supper’s ready.’

It was late. There was still a bit of light but in half an hour it would be dark. I wasn’t too happy about that.

‘Tell them I’m not their son any more and you’re their only child.’

My sister frowned. ‘And you’re not my brother either?’

‘No.’

‘So I can have the room to myself and I can have all your comics?’

‘No, that’s got nothing to do with it.’

‘Mama says if you don’t come, she will. And she’ll spank you.’ She beckoned me down.

‘I don’t care. Anyway, she can’t get up the tree.’

‘Yes she can. Mama’ll climb up.’

‘Well, I’ll throw stones at her.’

She got on her saddle. ‘She’ll be cross, you know.’

‘Where’s papa?’

‘He’s not there.’

‘Where is he?’

‘He’s gone out. He won’t be back till late.’

‘Where’s he gone?’

‘I don’t know. Are you coming?’

I was starving. ‘What’s for supper?’

‘Purée and eggs,’ she said as she rode off.

Purée and eggs. I loved both of them. Especially when I stirred them together and they became a delicious mush.

I jumped down from the carob. ‘All right, I’ll come. Just for this evening, though.’

At supper nobody talked.

It was as if there had been a death in the family. My sister and I ate sitting at the table.

Mama was washing the dishes. ‘When you’ve finished go straight to bed and no grumbling.’

Maria asked: ‘What about the television?’

‘No television. Your father’ll be back soon and if he finds you up there’ll be trouble.’

I asked: ‘Is he still very cross?’

‘Yes.’

‘What did he say?’

‘He said if you go on like this, next year he’ll take you to the friars.’

Whenever I did anything wrong papa always threatened to send me to the friars.

Salvatore and his mother went to the monastery of San Biagio now and then because his uncle was the friar guardian. One day I had asked Salvatore what it was like at the friars.

‘Lousy,’ he had replied. ‘You spend all day praying and in the evening they shut you up in a room and if you need a pee you can’t do it and they make you wear sandals even if it’s cold.’

I hated the friars, but I knew I would never go there because papa hated them even more than I did and said they were pigs.

I put my plate in the sink. ‘Won’t papa ever get over it?’

Mama said: ‘If he finds you asleep he might.’

* * *

Mama never sat at table with us.

She served us and ate standing up. With her plate resting on the fridge. She spoke little and stayed on her feet. She was always on her feet. Cooking. Washing. Ironing. If she wasn’t on her feet, she was asleep. The television bored her. When she was tired she flopped on her bed and went out like a light.

At the time of this story mama was thirty-three. She was still beautiful. She had long black hair that reached halfway down her back and she let it hang loose. She had two dark eyes as big as almonds, a wide mouth, strong white teeth and a pointed chin. She looked Arabian. She was tall, shapely, she had a big bosom, a narrow waist and a bottom that made you long to touch it and wide hips.

When we went to the market in Lucignano I saw how the men’s eyes would be glued to her. I saw the fruit-seller nudge the man on the next stall and they looked at her bottom and then raised their heads to the sky. I held her hand, I clutched onto her skirt.

She’s mine, leave her alone, I felt like shouting.

‘Teresa, you give a man evil thoughts,’ said Severino, the guy who brought the water tanker.

Mama wasn’t interested in these things. She didn’t see them. Those lecherous looks just slipped off her. Those peeks into the V of her dress left her cold.

She was no flirt.

It was so humid you couldn’t breathe. We were in bed. In the dark.

‘Do you know an animal that starts with a fruit?’ my sister asked me.

‘What?’

‘An animal that starts with a fruit.’

I started thinking about it. ‘Do you know?’

‘Yes.’

‘Who told you?’

‘Barbara.’

I couldn’t think of anything. ‘There’s no such thing.’

‘Yes there is, yes there is.’

I had a stab. ‘A plumber.’

‘That’s not an animal. It doesn’t count.’

My mind was a blank. I ran through all the fruit I knew and stuck bits of animals on the end but nothing came of it.

‘A peachinese?’

‘No.’

‘A pearanha?’

‘No.’

‘I don’t know. I give up. What is it?’

‘I’m not telling you.’

‘You’ve got to tell me now.’

‘All right, I’ll tell you. An orang-utan.’

I slapped myself on the forehead. ‘Of course! An orange utan! It was dead easy. What a fool …’

‘Good night,’ said Maria.

‘Good night,’ I replied.

I tried to sleep, but I wasn’t sleepy, I tossed and turned in bed.

I looked out of the window. The moon was no longer a perfect ball and there were stars everywhere. That night the boy couldn’t turn into a wolf. I looked towards the mountain. And for an instant I thought a light was glimmering on the top.

I wondered wh

at was happening in the abandoned house.

Maybe the witches were there, naked and old, standing round the hole laughing toothlessly and maybe they were dragging the boy out of the hole and making him dance and pulling his pecker. Maybe the ogre and the gypsies were there cooking him on hot coals.

I wouldn’t have gone up there at night for all the tea in China. I wished I could turn into a bat and fly over the house. Or put on the old suit of armour that Salvatore’s father kept by the front door and go up onto the hill. Wearing that I would be safe from the witches.

Three

In the morning I woke up calm, I hadn’t had nightmares. I stayed in bed for a while, with my eyes closed, listening to the birds. Then I started seeing the boy rising up and stretching out his arms again.

‘Help!’ I said.

What an idiot I was! That’s why he had sat up. He had been asking me for help and I had run away.

I went out of the room in my underpants. Papa was tightening the coffee pot. Barbara’s father was sitting at the table.

They turned round.

‘Good morning,’ said papa. He wasn’t angry any more.

‘Hello Michele,’ said Barbara’s father. ‘How are you?’

‘Fine.’

Pietro Mura was a short, stocky man, with a big black moustache that covered his mouth and a square head. He was wearing a black suit with thin white stripes and a vest. He had been a barber in Lucignano for a number of years, but business had never been good and when a new salon had opened with manicuring and modern hairstyles he had shut up shop and now he was a small farmer. But in Acqua Traverse he was still known as the barber.

If you needed a haircut you went round to his house. He would sit you down in the kitchen, in the sun, next to the cage with the goldfinches in it, open a drawer and take out a rolled-up cloth in which he kept his combs and his well-oiled scissors.

Pietro Mura had short thick fingers like toscano cigars that barely fitted into the scissors, and before he started cutting he would open the blades and pass them over your head, in front and behind, like a water diviner. He said that when he did this he could feel your thoughts, whether they were good or bad.

And I, when he did this, used to try and think only of nice things like ice-creams, falling stars or how much I loved mama.

He looked at me and said: ‘What’re you trying to be, a longhair?’

I shook my head.

Papa poured the coffee into the good cups.

‘He drove me up the wall yesterday. If he carries on like this I’m sending him to the friars.’

The barber asked me: ‘Do you know how friars have their hair cut?’

‘With a hole in the middle.’

‘That’s right. You’d better be good then.’

‘Come on, get dressed and have breakfast,’ said papa. ‘Mama’s left you the bread and milk.’

‘Where’s she gone?’

‘To Lucignano. To the market.’

‘Papa, I’ve got something to tell you. Something important.’

He put on his jacket. ‘You can tell me this evening. I’m going out. Wake up your sister and warm the milk.’ In one gulp he downed his coffee.

The barber drank his and they both went out of the house.

After getting Maria’s breakfast I went down into the street.

Skull and the others were playing soccer in the sun.

Togo, a little black and white mongrel, was chasing the ball and getting under everyone’s feet.

Togo had appeared in Acqua Traverse at the beginning of the summer and had been adopted by the whole village. He had made himself a bed in Skull’s father’s shed. Everybody gave him leftovers and he had become a great fat thing with a stomach swollen like a drum. He was a nice little dog. When you stroked him or took him indoors he became excited and squatted down and peed.

‘You go in goal,’ Salvatore shouted to me.

I went. Nobody else liked being goalkeeper. I did. Maybe because I was better with my hands than with my feet. I liked jumping, diving, rolling in the dust. Saving penalties.

The others just wanted to score goals.

I let in a hatful that morning. Either I fumbled the ball or I was late getting down to it. My mind was elsewhere.

Salvatore came over to me. ‘What’s the matter, Michele?’

‘The matter?’

‘You’re playing terribly.’

I spat on my hands, spread my arms and legs and narrowed my eyes like Zoff.

‘Now I’ll save it. I’ll save everything.’

Skull beat Remo and fired in a hard direct shot. It was well struck, but an easy one, the sort you can punch away one-handed or clutch to your stomach. I tried to grab it but it slipped through my hands.

‘Goal!’ roared Skull and punched the air as if he had scored against Juventus.

The hill was calling me. I could go. Papa and mama were out. As long as I was back by lunchtime.

‘I’m not in the mood for football,’ I said and went off.

Salvatore ran after me. ‘Where are you going?’

‘Nowhere.’

‘Shall we go for a ride?’

‘Later. There’s something I have to do now.’

I had run away and left everything like this: the corrugated sheet thrown to one side with the mattress, the hole uncovered and the rope hanging down inside.

If the guardians of the hole had come, they must have seen that their secret had been discovered and they would get me.

What if he wasn’t there any more?

I must pluck up courage and look.

I leaned over.

He was rolled up in the blanket.

I cleared my throat. ‘Hi … Hi … Hi … I’m the boy who came yesterday. I came down, remember?’

No reply.

‘Can you hear me? Are you deaf?’ It was a stupid question. ‘Are you ill? Are you alive?’

He bent his arm, raised his hand and whispered something.

‘What? I didn’t catch that.’

‘Water.’

‘Water? Are you thirsty?’

He raised his arm.

‘Wait a minute.’

Where was I going to find water? There were a couple of paint buckets, but they were empty. In the washing trough there was a little water, but it was green and crawling with mosquito larvae.

I remembered that when I had gone in to get the rope I had seen a drum full of water.

‘I’ll be right back,’ I said, and climbed through the little window over the door.

The drum was half full, but the water was clear and didn’t smell. It seemed all right.

In a dark corner, on a wooden plank, there were some cans, some half-burned candles, a saucepan and some empty bottles. I took one bottle, walked two paces and stopped. I went back and picked up the saucepan.

It was a shallow pan covered in white enamel, with a blue rim and handles, and red apples painted round the outside. It was just like the one we had at home. We had bought ours with mama at Lucignano market, Maria had chosen it from a pile of saucepans on a stall because she liked the apples.

This one looked older. It hadn’t been properly washed, there was still some stuff stuck on the bottom. I ran my forefinger over it and brought it up to my nose.

Tomato sauce.

I put it back and filled the bottle with water, closing it with a cork stopper, took the basket and climbed out.

I grabbed the rope, tied the basket to it and put the bottle inside.

‘I’ll lower it down to you,’ I said. ‘Take it.’

With the blanket round him, he groped for the bottle in the basket, uncorked it and poured the water into the saucepan without spilling a drop, then he put it back in the basket and gave a tug on the cord.

As if it was something he always did, every day. Since I didn’t take it back he gave a second tug and grunted something angrily.

As soon as I had pulled it up he lowered his head and without lifting the saucepan sta

rted to drink, on all fours, like a dog. When he had finished he crouched down on one side and didn’t move again.

It was late.

‘Well … goodbye.’ I covered up the hole and went away.

While I was cycling towards Acqua Traverse, I thought about the saucepan I had found in the kitchen.

I found it strange that it was the same as ours. I don’t know why, maybe because Maria had chosen it from so many. As if it was special, more beautiful, with those red apples.

I arrived home just in time for lunch.

‘Hurry up, go and wash your hands,’ said papa. He was sitting at the table next to my sister. They were waiting for mama to drain the pastasciutta.

I dashed into the bathroom and rubbed my hands with the soap, parted my hair on the right and joined them while mama was filling the plates with pasta.

She wasn’t using the saucepan with the apples on it. I looked at the dishes drying on the sink, but I couldn’t see it there either. It must be in the kitchen cabinet.

‘In a couple of days somebody’s coming to stay with us,’ said papa with his mouth full. ‘You must both be good. No crying and shouting. Don’t show me up.’

I asked: ‘Who is this somebody?’

He poured himself a glass of wine. ‘A friend of mine.’

‘What’s his name?’ my sister asked.

‘Sergio.’

‘Sergio,’ Maria repeated. ‘What a funny name.’

It was the first time anyone had ever come to stay with us. At Christmas my uncles and aunts came but they hardly ever stayed the night. There wasn’t enough room. I asked: ‘And how long is he staying?’

Papa filled his plate again. ‘For a while.’

Mama put the little slice of meat in front of us.

It was Wednesday. And Wednesday was meat day.

The meat that’s good for you, the meat my sister and I couldn’t stand. I, with a great effort, could get that tough tasteless bit of shoe-leather down, but my sister couldn’t. She would chew it for hours till it became a stringy white ball that swelled up in her mouth. And when she really couldn’t stand it any more she would stick it on the underside of the table. There the meat fermented. Mama just couldn’t understand it. ‘Where’s that smell coming from? What on earth can it be?’ Till one day she took out the cutlery drawer and found all those ghastly pellets stuck to the boards like wasps’ nests.

Let the Games Begin

Let the Games Begin I'm Not Scared

I'm Not Scared Steal You Away

Steal You Away Me and You

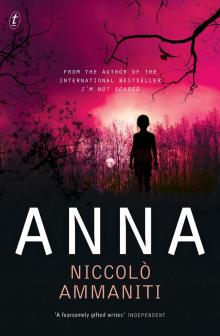

Me and You Anna

Anna