- Home

- Niccolò Ammaniti

Let the Games Begin Page 15

Let the Games Begin Read online

Page 15

‘And him?’ Silvietta bent down over Antonio's body. ‘What will we do with him?’

‘We'll tie and gag him. And then we'll hide him somewhere.’

32

As he followed the waiter towards the Royal Villa, Fabrizio cursed to himself. He didn't have time to waste. He had a plane to catch, and the idea that he had to speak to Sasà Chiatti bothered him. It was ridiculous. He'd been in the presence of Sarwar Sawhney, a Noble Prize winner, without feeling any sort of particular emotions, and now that he was about to meet an insignificant fellow like Chiatti his heart was racing? The truth was that rich and powerful men made him feel insecure.

He walked into the Villa and was surprised. He had expected anything except that the residence would be furnished in minimalist style. The big living area was a simple cement floor. In a fireplace made of uncut stone burned a big block of wood. Nearby, four armchairs in seventies style and a ten-metre-long solid-steel table with an antique lampshade hanging overhead. Two thin Giacometti statues. In another corner, as if they had been forgotten, were four Fontana eggs, and on the whitewashed walls some Cretti by Burri.

‘This way . . .’ The waiter pointed towards a long corridor. He led him into a kitchen covered in Morrocan majolicas. A Bang & Olufsen stereo was playing the romantic notes of Michael Nyman's The Piano.

A big stocky woman, with a mahogany-coloured helmet of hair, was juggling saucepans over the stove. In the centre of the room, sitting around a rough wooden table, were Salvatore Chiatti, an albino sylph, a decrepit old man wearing a moth-eaten old colonial outfit, a monk and Larita the singer.

They were eating what appeared to be rigatoni all'amatriciana, with heaps of pecorino cheese grated over the top.

Fabrizio had the presence of mind to say: ‘Hello, everyone.’

Chiatti was wearing a beige velvet jacket with patches on the elbows, a checked flannel shirt and a red handkerchief tied around that limited the length of neck that nature had granted him. He wiped his mouth and threw his arms open as if he had known Fabrizio for a hundred years.

‘Here he is, that wonderful writer! What a pleasure to have you here. Please join us. We're eating something simple. I hope you didn't eat anything from the buffet? We'll leave that junk for the VIP guests, right, Mum?’

He turned towards the barge-arse at the stove. The woman, feeling awkward, cleaned her hands on her apron and nodded hello.

‘We're simple people. And we eat pasta. Take a seat. What are you waiting for?’

Fabrizio's first impression of Chiatti was that he was affable, with a big jovial smile; but he was also aware that he was giving orders, and he didn't like being disobeyed.

The writer pulled up a chair from next to the wall and sat in a corner between the old man and the monk, who made room for him.

‘Mum, fill a plate as God commands for Mr Ciba. He looks a little ruffled to me.’

A second later Fabrizio found a gigantic serving of smoking rigatoni in front of him.

Chiatti grabbed a flask of wine and poured Ciba a glass.

‘Let's get the introductions out of the way. He . . .’ He pointed at the shrivelled old guy. ‘ . . . is the great white hunter, Corman Sullivan. Did you know that this man met the writer . . . what's his name?’

‘Hemingway . . .’ said Sullivan, and began coughing and shaking all over. Clouds of dust rose up from his clothes. When he recovered, he squeezed Fabrizio's hand weakly. He had long fingers, covered in depigmented spots.

The white hunter reminded Ciba of someone. Of course! He was the spitting image of Ötzi, the Similaun Man, the hunter found frozen in a glacier of the Alps.

Chiatti pointed at the sylph. ‘This is my girlfriend, Ecaterina.’ The girl tilted her head, in greeting. She looked like the Snow Queen in a Scandinavian saga. She was so white she looked as if she'd been dead for three days. Through her skin you could see the blood running dark in her veins. Her hair, fiery red, was a mane around her flat face. She didn't have eyebrows and her throat was as thin as a greyhound's. She must have weighed about twenty kilos.

When Fabrizio heard her name, he remembered. She was the famous albino model Ecaterina Danielsson. She was on the covers of fashion magazines the world over. She was undoubtedly the most morphologically different human being compared to Chiatti that nature had ever created.

‘And this here . . .’ He pointed at the monk. ‘You should recognise him. It's Zóltan Patrovic!’

Of course Fabrizio recognised him. Who didn't know the unpredictable Bulgarian chef, owner of the restaurant Le Regioni ? But he'd never seen him up close.

Who did he remind him of? Yes, Mefisto, Tex Willer's sworn enemy.

Fabrizio had to lower his gaze. The chef's eyes seemed to sink inside him and sneak into his thoughts.

‘And last but not least, our Larita, who will do us the great honour of singing for us this evening.’

Finally Ciba found himself looking at a human being.

She's pretty, he said to himself as he shook her hand.

Chiatti pointed at Ciba: ‘And do you all know who he is?’

Fabrizio was about to say that he was nobody, when Larita smiled, showing her slightly separated incisors, and said: ‘He's the greatest. He wrote The Lion's Den. I loved it. But my favourite is Nestor's Dream. I've read it three times. And each time I cried like a little girl.’

A dart had hit a bullseye in the middle of Fabrizio's chest. His legs, for an instant, gave way, and he almost collapsed on the Similaun man's shoulder.

Finally, someone who understood him. That was his best work. He'd squeezed himself like a lemon to finish it. Every single word, every comma, had been painstakingly extracted from him. Whenever he thought of Nestor's Dream, an image came to mind. It was as if an aeroplane had exploded in flight and the remains of the aircraft had been spread across a radius of thousands of kilometres over a flat and sterile desert. It was up to him to find the pieces and put the aircraft's fuselage back together. The complete opposite of The Lion's Den, which had come out painlessly, as if it had written itself. He was convinced that Nestor's Dream was his most mature and complete work. And yet its reception by his readers had been, to put it mildly, lukewarm, and the critics had torn him to shreds. So when he heard the singer say those things, he couldn't help but feel a deep sense of gratitude.

‘That's very kind of you. I'm pleased to hear that. Thanks,’ he said to her, feeling almost embarrassed.

If you walked past Larita in the street, you would hardly notice her, but if you looked at her carefully you would see that she was very pretty. Each part of her body was well proportioned. Her neck, her shoulders neither too wide nor too narrow, her thin wrists, her slim, elegant hands. Her black bob hid her forehead. Her small nose and that mouth – just a tad too wide for her oval-shaped face – expressed a shy, sincere likeability. But what stood out were her big, hazelnut-colored eyes, with gold flecks that in the moment seemed a little lost.

How weird that, between parties, presentations, concerts and salons, Ciba had met just about everyone, and yet not once had he come across this singer. He had read somewhere that she kept to herself and minded her own business. She didn't enjoy the spotlight.

A bit like me.

Fabrizio had also appreciated the story of her religious conversion. He, too, had felt a strong calling back to his faith. Larita was a thousand times better than that hopeless gang of Italian singers. She stayed at home in a house in the Tuscan–Emilian Appenine mountains and created . . .

Just like I should do.

The same old vision materialised in his mind. The two of them together in a wooden hut. She would play and he would write. Minding their own business. Perhaps a child. Definitely a dog.

Larita flicked her fringe. ‘There's no reason to thank me. If something is beautiful, it's beautiful, full stop.’

I'm an idiot. I was about to leave and the love of my life is here.

Chiatti applauded, amused. ‘Well. See what a beautiful fan

I found for you? Now, to thank me you'll do me a favour. Have you got a poem?’

Fabrizio frowned. ‘What do you mean?’

‘A poem, to read before my speech. I'd like to be introduced by one of your poems.’

Larita came to his aid. ‘He doesn't write poetry, as far as I know.’

Fabrizio smiled at her, then turned to Chiatti seriously: ‘Exactly. I have never written a poem in my whole life.’

‘Couldn't you write just one? Even a short one?’ The entrepreneur looked at his Rolex. ‘Can't you jot one down in twenty minutes? It'd only have to be a couple of lines.’

‘A little poem about hunters would be wonderful. I recall Karen Blixen . . .’ Corman Sullivan stepped in, but was unable to continue as he was overcome with a coughing fit.

‘No. I'm sorry. I don't write poems.’

Chiatti flared his nostrils and made a fist, but his voice remained polite. ‘All right, I have an idea. You could read someone else's poem. I should have a copy of Pablo Neruda's poetry here somewhere. Would that work for you?’

‘Why should I read a poem by another author? There are hundreds of actors out there who would slaughter each other for a chance to do it. Get one of them to read it.’ Fabrizio was beginning to get just a bit pissed off.

Zóltan Patrovic suddenly tapped his glass with a knife.

Fabrizio turned around and was captured by his magnetic gaze. What a singular sensation: it seemed as if the chef's eyes had expanded and were now covering his whole face. Beneath the black hood it was like two enormous ocular globes were staring at him. Fabrizio tried to look away, but was unable to. So he tried to close his eyes and break the spell, but failed again.

Zóltan placed his hand on the writer's forehead.

Instantly, as if someone had pushed it forcefully into his memory, Fabrizio was reminded of a forgotten episode from his childhood. His parents, in summer, were leaving on a sailing boat, and they left him with cousin Anna in a mountain cottage at Bad Sankt Leonhard, in Carinthia, with a family of Austrian farmers. It was a beautiful area, with pine-covered mountains and green fields where piebald cows grazed happily. He wore the typical leather shorts, with braces, and ankle boots with red laces. One day, while he and Anna were hunting for mushrooms in the forest, they had got lost. They were unable to remember where to go. They had kept walking around and around, hand in hand, their fear growing as the night stretched out its tentacles between the identical-looking trees. Luckily, at some point, they had found themselves standing in front of a little chalet hidden amidst the pine trees. Smoke was coming from the chimney and the windows were lit. They knocked and a woman with a blonde chignon sat them down at a table, along with her three children, and gave them Knödel, big balls of bread and meat floating in broth, to eat. Mamma mia, they were so soft and delicious!

Fabrizio realised that he desired nothing more in life than a couple of Knödel in broth. After all, it didn't cost him anything to say yes to Chiatti, and later he could always find an Austrian restaurant.

‘Okay, I'll read it. No problem. I beg your pardon, but do you know whether there is an Austrian restaurant near here somewhere?’

33

Antonio's head bounced on each step and the muffled sound echoed against the vaulted ceiling of the staircase that disappeared into the bowels of the earth. Murder and Zombie dragged the head waiter by his ankles.

The leader of the Beasts, at the head of the gang, shone an electric torch on the walls of the tunnel carved in the tuff rock. Greenish mould and spider webs were all they saw. The air was humid and smelled of wet dirt.

Mantos didn't have the vaguest idea where the stairway led. He had opened an old door and slipped in before anyone could see them.

Silvietta stopped to look at Antonio. ‘Guys, won't all those bangs to the head hurt him?’

Saverio turned to her. ‘He's hard-headed. We're almost there.’

Murder was tired. ‘Thank goodness! We've been going down for ages. It's like a mine.’

In the end they came to a cave. Zombie turned on two torches screwed to the walls, and a part of the room brightened.

It wasn't a cave, but a long room with a low ceiling and rows of rotten barrels and piles of dusty bottles. On each side of the room a rusty grating closed off a narrow tunnel that led who knows where.

‘This place is perfect for a Satanic ritual.’ Murder lifted a bottle and dusted off the label: ‘Amarone 1943.’

‘They must be the royal cellars,’ Silvietta suggested.

‘You don't perform Satanic rituals in a cellar. At most, in a deconsecrated church or in the open air. In any case, by the light of the moon.’ Mantos pointed at a corner underneath the torches: ‘Come on, let's dump my cousin and get out of here. We don't have time to waste.’

Zombie, off to one side, was studying a grate. Silvietta went up to him. ‘That's weird! Four identical tunnels.’ She stuck her hand through the bars. ‘I can feel warm air. I wonder where it comes from?’

Zombie shrugged. ‘Who cares?’

‘You reckon it's safe to leave him here? He won't wake up again, will he?’

‘I don't know . . . And I don't really care that much either.’ Zombie walked away stiffly.

Silvietta looked after him, feeling perplexed. ‘What's your problem? Are you pissed off?’

Zombie started walking up the stairs without answering.

Mantos followed him. ‘Let's move.’

The Beasts had climbed one hundred steps when they heard a muffled noise coming from below. Murder stopped. ‘What was that?’

‘Antonio must have woken up,’ said Silvietta.

Mantos shook his head. ‘Not likely. He'll sleep a couple of hours, at least. Sedaron is strong stuff.’

And they kept climbing.

If, instead, they had gone back down, they would have found Antonio Zauli's body missing.

Speech by Salvatore Chiatti to the Guests

34

Fabrizio Ciba, the book of poems by Neruda in his pocket, was walking in circles behind a bandwagon that had been transformed into a stage for the occasion. They had put a microphone on him and explained that in a few minutes he would go up and read the poem. He couldn't work out why he'd accepted. He turned down everyone. Even the most aggressive press officers. Even political leaders. Even the advertising executives that promised him a pile of cash.

What the fuck had come over him? It was like someone had forced him to accept. And what's more, Pablo Neruda made him sick.

‘Are you ready?’

Fabrizio turned around.

Larita was walking up to him, holding a cup of coffee in her hand. She had a smile that made you want to hug her.

‘No. Not at all,’ he admitted, feeling distressed.

She began scraping at the sugar stuck to the bottom of the cup and, without looking at him, confessed: ‘Once I came to Rome to hear you read excerpts from The Lion's Den at the Basilica di Massenzio.’

Fabrizio didn't expect that. ‘Why didn't you come to say hi?’

‘We'd never met. I'm shy, and there was a huge queue of people wanting your autograph.’

‘Well, that was a bad decision. This is serious.’

Larita laughed, moving closer. ‘Do you want to know something? I don't like these sorts of parties. I would never have come, if Chiatti hadn't offered me so much money. You know,’ the singer continued, ‘with the money I want to lay the foundations for a sanctuary for cetaceans near Maccarese.’

Fabrizio was caught off-guard and took a weak stab. ‘It would have been a bad decision not to come, because we never would have met.’

She began playing with the coffee cup. ‘That's true.’

‘Listen, have you ever been to Majorca?’

Larita was shocked. ‘I can't believe you're asking me that. Do you know Escorca, on the north of the island?’

‘It's near my house.’

‘I'll be spending six months there to record my new album.’

F

abrizio put his hand over his mouth, feeling excited. ‘I've got a country house in Capdepera . . . !’

Bad luck would have it that, at that moment, the guy who had microphoned him appeared. ‘Doctor Ciba, you need to go on stage. It's your turn.’

‘One second,’ Fabrizio said, gesturing to him to stay back. Then he laid a hand on Larita's arm. ‘Listen, promise me something.’

‘What?’

He looked her straight in the eyes. ‘At these parties everyone plays a part, people only just brush against each other. That hasn't happened to us. You said before that you liked Nestor's Dream. Now you tell me you're going to Majorca, where I will go to write and find some peace. You have to promise me that we'll see each other again.’

‘I'm sorry, Doctor Ciba, you really need to get up there.’

Fabrizio stared daggers at the guy and then turned to Larita: ‘Can you promise me that?’

Larita nodded. ‘Okay. I promise.’

‘Wait for me here . . . I'll go, look like a dickhead, then come back.’

Fabrizio, elated, went up the stairs that led to the bandwagon, without turning to look at her. He found himself on a small stage, opposite the courtyard with the Italian-style garden packed full of guests.

Ciba waved to the crowd, ran his fingers through his hair, smiled slightly, pulled out the book of poems and was just about to read when he saw Larita making her way through the crowd and moving closer to the stage. His mouth suddenly went dry. He felt as if he'd gone back to the days of high-school recitals. He put the book back and said bashfully: ‘I had planned on reading you a poem by the great Pablo Neruda, but I've decided to recite one of my own.’ Pause. ‘I dedicate it to the princess who doesn't break promises.’ And he began reciting:

My belly will be the coffer

where I will hide you from the world.

I will fill my veins

with your beauty.

I will make my breast the cage

for your sorrows.

I shall love you as the clownfish loves the sea anemone.

I shall sing your name here, now, at once.

Let the Games Begin

Let the Games Begin I'm Not Scared

I'm Not Scared Steal You Away

Steal You Away Me and You

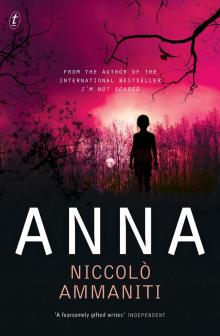

Me and You Anna

Anna